Nicholl (1980) has provided alchemical equivalents for various characters in the play, drawing upon numerous engravings and texts to show Shakespeare's inspiration by alchemy. I would add that the relationship may have gone both ways. The engravings are mostly from the period immediately after Shakespeare, starting with those produced by Maier, a German physician and alchemist. According to Frances Yates (1964), Maier spent the years 1612-1614 in London staying with Robert Fludd, another physician/alchemist. Fludd later used the same German publisher as Maier. In London Meier could hardly have missed performances of Shakespeare's plays, given their fame and their references to healing and magic. In 1618, Maier published his Atalanta Fugiens--Atalanta Fleeing, where the fleet-footed Atalanta of Greek myth is a metaphor for Mercury, who in alchemy is both a god and a metal--and neither, but rather a spirit in metals and in many other things.

Cobb (1984) has applied Maier's engravings to The Tempest, another play he could have seen. Many engravings, more than I have space for, apply to Lear. I speculate that seeing the plays might have influenced Maier’s imagery. Be that as it may, the mottoes and epigrams in Maier’s texts mostly derive from long before Shakespeare, as far back as 10th century Muslim Spain.

Figure 5. Emblem 14 of Michael Maier, Atalanta Fugiens, Oppenheim (in what is now Germany), 1618. Maier's associated motto: "Here is the Dragon that devours its own tail."

With that caveat, let us turn to the illustrations. As Nicholl (1980) shows, Lear begins as the poisonous dragon: As he tells Kent, "Come not between the dragon and his wrath" (I.i.123). The corresponding engraving is of a dragon eating its tail (Fig. 5 above; de Rola 1988, 78). Maier in the attached epigram speaks of a "hunger" that "taught men to feed on human flesh." But this dragon not only feeds on its own kind--it "becomes food for itself." Similarly, Lear's actions, directed against others, mostly work against himself. Maier goes on, "This dragon will have to be conquered... /Till it...kills itself and generates itself again" (de Jong 1969, 129).

In ancient Greece the tail-eating snake or dragon was the uroboros, a symbol of eternal destruction and renewal. These are two aspects of alchemical Mercury, poison and medicine. The uroboros, as a single snake rather than Mercury's double snake, was associated with Saturn (de Jong 1969, 192). Saturn to the Greeks was Chronos, which the Renaissance identified with Kronos, time. The snake eating its tail was “all-devouring time,” which consumes even itself. But Saturn, like Mercury, has two aspects, death and wisdom. Thus in the 4th century Pistis Sophia, the uroboros represented the "outer darkness" encircling the cosmos, while it was also the "sun-disc…which ascended to the seven powers," and as such was a symbol of light (de Jong 1969, 134). Lear, as the play will demonstrate, has a similar duality.

Figure 6. Ophite Diagram reconstructed by Liesegang, 1955, from description by Origen, ontra Celsius, 5th century. Leviathan, the uroboros tail-eating snake, is between Saturn and Paradise.

For the Ophites, in an account by Origen (available to Shakespeare if he knew where to look), the uroboros snake was Leviathan, encircling the cosmos just beyond Saturn, thereby signifying its lordship over our world. It also forms the barrier between the cosmos, ruled by its malevolent forces, and Paradise (Fig. 6; Rudolph 1983, 69). Thus beyond the negative side of the world-snake lay the positive, as will be true of Lear.

Figure 7, left, The world-snake in the form of an amulet. Drawing on papyrus, 3rd century. Figure 8, right, tail-eating snake, drawing in 11th centur manuscript, copied from 4th century Egyptian papyrrus.

Amulets seem to have been made to this god for protection, the drawings in Fig. 7 (Rudolph 1983, 223) and Fig. 8 (Rudolph 1983, 70), from the 3rd and 4th century, may have been prototypes for such amulets. As the name and seal "of the might of the great God," the amulet shown in Fig. 7 protects its owner "against demons, against spirits, against all illness and all suffering" (Rudolph 1983, 223). The inscription contains magical words including "Yaeo" (Yao, a variant on Yahweh; Unger 1992, 152-153) and the formula, "Protect me, NN, body and soul from all injury." Presumably the god was credited with the power both to protect and to hurt, in the manner of a great but capricious king such as Lear. Along these lines the snake in Fig. 8 is black on top and white on the bottom. The inscription reads, “One is the all” (Rudolph 1983, 70). An inscription on the same papyrus page says, “The snake is the one; it has two symbols, good and evil” (Roob 201, 422). Thus black is for earth and evil, white for heaven and good.

Later Lear uses the image of the snake to characterize Goneril; she is "most serpent-like" (II.ii.350). She has her father's destructive Mercury-venom.

Figure 9. "The Wolf devoured the King and, cremated, restored him to life." Emblem 24 of Michael Maier, Atalanta Fugiens, Oppenheim 1618.

Goneril's face reminds Lear of another animal: "thy wolvish visage" (I.iv.300). Maier does have an appropriate picture of a wolf. This animal corresponds to alchemical antimony (de Jong 1969, 188); he shows it eating the king's dead body (Fig. 9; de Rola 1988, 83). The background shows the wolf's fiery destruction and the king's rebirth. The picture shows an alchemical sequence: first antimony dissolves impure gold; then the antimony is burnt off and the purified gold remains. It is also a fitting picture of Lear’s progress. This dead king in the body of the wolf corresponds to Lear when he is the power of his elder daughters. The destruction of that power, then, brings about Lear's rebirth.

Figure 10. "The fruit of human Wisdom is the Tree of Life." Emblem. 26 Michael Maier, Atalanta Fugiens, Oppenheim 1618.

Cordelia, in contrast, is the life-giving Mercury, pictured as a beautiful maiden (Fig. 10 above; de Rola 1988, 84). The right banner says "length of days and health"; the left is "honor and infinite riches," both from Proverbs 3:16 (de Jong 1969, 195). She is Sapienta (Latin), Sophia (Greek), or Wisdom. Nicholl quotes descriptions of Mercury ("most dear...made altogether vile," "precious and of small account") similar to those of Cordelia ("most lov'd, despised" (I.i.253), "unprized, precious" (I.i.261)). "Mercury," another text declares, "is a pure virgin who meets all her wooers in foul garments, in order that she may be able to distinguish the worthy from the unworthy" (Nicholl 1980, 170). In the play, Burgundy rejects Cordelia after her disinheriting, but France does not. Thus do the suitors reveal their true merits.

Figure 11, Mercury as masculine jester figure. From Michel Maier, Lusus scrius, Oppenheim 1616.

Life-giving Mercury also has a masculine image, typically that of the god Mercury, with his double-snaked staff. An engraving by Meier (Fig. 11; de Rola 1988, 64) suggests Lear's Fool, with a jester-like Mercury before a king-like elder. In Maier’s fable, the cow, the sheep, the goose, the oyster, the bee, the silkworm, the flax-plant, and Mercury all argue their merits to a human judge. Mercury, as the elixor or universal medicine, of course wins. The Judge proclaims: “Thou so much exceedest thy competitors as the Sun the Planets; thou art the miracle, splendour, and light of the world” (de Rola 1988, 69). An analogy with Christ would seem to be implied.

Nicholl also quotes alchemical dialogues that capture the parallel to Lear's Fool: Mercury, the spirit corresponding to the metal, calls the alchemist blind and a fool, "for thou canst not see thyself" (1980, 181). Ben Johnson parodied such dialogues in his plays, Nicholl shows; but they inspired Shakespeare. This is the Mercury that Jung called both "a ministering and helpful spirit" and "an elusive, deceptive, teasing goblin who drove the alchemists to despair" (180). Other characters that fit this description are Midsummer Night Dream’s Puck and The Tempest’s Ariel.

Figure 12. "The King is bathed, sitting in the Laconian bath, and is freed from his black bile by Pharus." Emblem 28 of Michael Maier, Atlalata Fugiens, Oppenheim 1618.

For Lear's descent into madness, Nicholl gives us Maier's engraving of an old king in an oven (Fig. 12; de Rola 1988, 85). He quotes the alchemist Sendivogius: "This being done, let it be put in a furnace." (1980, 189). This stage in Lear comes with the storm, with its "sulph'rous and thought executing fires" (III.ii.4) and "all shaking thunder" (III.ii.6), along with an equal storm within. That is for Nicholl "the ultimate solvent" (188) by which Lear's identity dissolves.

Maier's epigram says "King Duenech ...swollen with bile, was horrible in his behavior" (de Jong 1969, 206). Maier explains that the King "is tortured by Saturnal somberness and a Martial fury" (207). All of this fits Lear. The alchemists' remedy is a sweat bath, which brings out "the excess of black bile" (209) which caused the melancholy. Psychologically, the point is that by purging oneself of one’s evils, one’s somberness and fury, getting them out, one is restored to health.

Yet there is another level of meaning, which comes out in a text cited by Jung (1970, 40 n. 229).

Then the most perfect body is taken and applied to the fire of the Philosophers; ...that body becomes moist, and gives forth a kind of bloody sweat, after the putrefaction and mortification, that is, a Heavenly Dew, and this dew is called the Mercury of the Philosophers, or Aqua Permanens" ("Epistola ad Hermannum," Theatre chemicum V, 894).In psychological terms, the ego when heated dies and decays, and what it gets out when heated is not just the evil, but that which will revitalize it. We shall see how Lear, his hold on reality faltering, gets out his own anger and despair in a cooler sort of bath, the storm, and in the isolated confinement of a leaky hut also brings out something new, a playful detachment from his former concerns, to be followed later by insight into higher truths. This is the kind of transformation which Basilides imagined for an enlightened demiurge.

Besides Maier, Nicholl uses other alchemical illustrations from an earlier time, the end of the 15th century. He discusses the Cantilena, a poem by the English alchemist George Ripley: An old king enters his mother's womb, to be reborn a child on its mother’s lap ascending to heaven. The womb is the same as the oven or bath, Lear's separation from his former self, out of which he is born anew. The virgin, of course, is Cordelia, who nourishes Lear with her words of love.

Figure 13. Saturn and his children. From "Thomas Aquinas," pseud, De Alchimea, early 16th century.

Similarly, Nicholl discusses one part of a watercolor of the early 16th century (Fig. 13; Roob 2001, 194), by an adept using the name "Thomas Aquinas." In the middle, a maiden pours water on a sleeping king. We know he is Saturn by the children he has swallowed, the elder planetary gods, emerging from his mouth. Nicholl likens the maiden to Cordelia waking the sleeping Lear with her tears. In the lower part of the picture a young king—either the same one, revitalized, or one of the sons, Jupiter--regenerates in a warm bath, another image for Cordelia's care. He holds the maiden's hands, hinting at a coming marriage (and a son, Apollo, signifying gold, according to Roob—also Christ, I think, whom Christianity merged with the pagan sun-god). Lear similarly wishes to be always with Cordelia.

Figure 14. Tranformation. From "Thomas Aquinas," pseud. De Alchimia, early 16th century.

Another 16th century watercolor, not discussed by Nicholl, seems to me to capture much of Lear's process (Fig. 14; Jung 1968, 281). It is from the same Alchimia series by the so-called "Thomas Aquinas." I see this picture as presenting a series of five stages, with the alchemist shown differently at each stage. At the bottom, at which I would call the stage of earth, the alchemist stands on the ground facing the soror (Latin for sister), his assistant. The two are in the positions, left and right, in which the alchemists frequently put the king and the queen. Above them are two animals, for him the lion and for her the ram. I think we can understand these animals by looking at Lear and Cordelia at the beginning of the play, with Lear's leonine roaring and Cordelia's butting against him, leading to Cordelia’s sacrifice of her inheritance, just as the ram is also the lamb sacrificed at passover. We can also understand the "keys to the work" which the two lower figures hold in their hands: it is their basic antagonism, domination, order, and flattery vs. freedom, love, and truth. Yet it is this antagonism which drives the ego's development to a new level of being and consciousness.

Astrologically both the lion and the ram are fire-signs (Roob 2001, 518). This energy, I submit, is the fire that heats the water in the tomb above them. We do not see the fire, admittedly, but other alchemical images have a fire at a similar point: compare Fig. 9, with its wolf-consuming fire, and Fig. 12, with its sweat bath. Other examples could be given. It seems to me that the animals, standing below the tomb and above their human counterparts, represent the alchemist in the second stage, that of fire, when the antagonism both inner and outer is at its peak.

The next stage is that of water: The alchemist floats in his tomb, while fluids run out the sides. Floating (solutio), death (mortificatio), and decay (putrefactio), resulting in the different liquids, suggest the suspension, death, and breaking into components of the old ego, which happen to Lear in the storm and the day following. In other illustrations of these stages a king and queen might be shown in the water, or a hermaphrodite merging the two.

In this process the alchemist's spirit rises and connects to heaven, the place of rest, helped by his angelic twin. In the play, Lear connects with Cordelia, who in his imagination, and also in life, helps his transition. This stage, of course, is that of air. Then the regenerated alchemist is shown enthroned in a tree, wearing a crown. It is a young but wise king--similar to the humbled Lear or the wizened Edgar. Astrologically the archer below him is Sagittarius (Roob 2001, 518), the third fire-sign, a heat source that keeps the kingly substance, Mercury as vapor, airborne in the alchemist's retort. It is a combination of air and fire, or perhaps a new stage above those of nature, which the alchemists called “the quintessence” or “ether,” the substance of heaven.

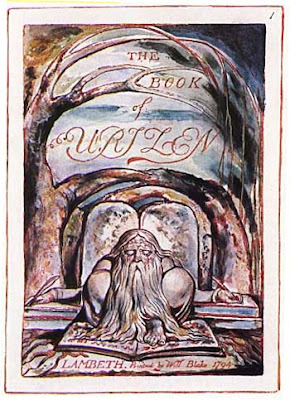

Perhaps surprisingly, we can see a similar process in the art of William Blake, working in a completely different era, 200 years after Shakespeare. Although Blake was not an alchemist, some of his engravings are very much in the alchemical tradition. Especially relevant are his renderings of his imaginary god Urizen (Your-reason), the demiurge in Blake's own Gnostic system, his reaction against the 18th century "age of reason." The title page of The First Book of Urizen shows the god writing; behind him are Moses' tablets, a clear reference to the Biblical Jehovah (Fig. 15; Roob 2001).

Figure 15, Title page of William Blake, First Book of Urizen, Lambeth, England, 1784.

The tablets are shaped like tombstones; Johovah’s original commandment was to Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, and when they disobeyed the punishment was exile to the world of mortality and death. The beginning of the word “Urizen” in the title curls like a snake, while the end has hellish whips (Erdmann 1974). The accompanying text, commenting on the void that begins Genesis, reads similarly:

…what DemonUrizen manages to create the world and soon is writing the Law, as in Fig. 15. Here his eyes are closed, and he reads both sides of a book with his toes. One might wonder whether he is blind, like Yaldabaoth. One side of the book seems to be letters; the other has pictures (Erdmann 1974). Blake’s caption to one print of this engraving says, “Which is the Way The Right or the Left?” (Erdmann 1974, 183). These two ways, I think, are those of the Word versus Nature. Urizen, of course, chooses the Word. The two ways correspond to the two sides of the book he is reading. With his right hand, he copies words; with his left, he etches pictures.

Hath formed this abominable void,

This soul-shudd’ring vacuum? Some said

“It is Urizen.” But unknown, abstracted,

Brooding, secret, the dark power hid. (Urizen I.1.3-7)

In Gnostic fashion, Blake also imagines the sons of Urizen, each representing one of the four traditional elements. Each, I think, corresponds to a stage in personal transformation, and especially to Lear’s transformation. In this sprit, it is also possible to interpret some of the pictures as Urizen himself at different times (as does Erdmann 1974)—although Urizon in this work does not get as far as the transformation.

Figure 16. Grodna (Earth), from William Blake, First Book of Urizen, 1784.One engraving, signifying earth, has a stone-faced, immovable figure squinting out onto the world (Fig. 16 above; Roob 2001, 192), like Lear on his throne at the beginning. The son is Grodna, who is “rent the deep earth, howling/ Amaz’d” (Urizen VIII.3.8-9). Applied to Urizen, the image corresponds to his presenting of the Law, “written in my solitude” (II.7.3.) while “hidden, set apart, in my stern counsels” (II.4.3). Those whom he would control, personifications of the seven deadly sins, chase him until he hides in the earth, where “a roof vast, petrific around/ On all sides he fram’d, like a womb” (III.7.1-2); there “Urizen laid in a stony sleep” (III.10.1-2).

Figure 17, Urizen, from William Blake, First Book of Urizen, 1784.

Another engraving paralleling Lear clearly refers to Urizen himself rather than a son. In this one, he is in shackles (Fig. 17 above; Roob 2001, 230), his inner torment turning him red-hot--similar to Lear after his elder daughters turn against him. Blake’s caption to one print of this engraving reads, “Frozen doors to mock The World: while they within torments uplock” (Erdmann 1974, 204). Erdmann comments on the chains: “forged by his own mind to mock the world, they lock him into his own torments,” words that apply well to Lear. In the poem, the fetters are made by Los, Urizen’s twin and relentless opponent. Los represents creative imagination; his name, as Erdmann points out, is “Sol” spelled backwards, implying both the sun and the soul. Fiery imagination has temporarily succeeded in fettering cold Reason. Blake describes Urizon’s agony:

Restless turn’d the Immortal inchain’d,The mood is like that of Lear made powerless by his daughters, reduced to seeking shelter in a hut. In the picture, the red glow emanating from Urizen’s head suggests the element of fire, expressing the torment of an enchained will.

Heaving dolorous, anguish’d unbearable;

Til a roof, shaggy wild, inclosed

In an orb his fountain of thought. (Urizen IV.5.1-4)

Figure 18, Fuzon (Fire), from William Blake, First Book of Urizen, 1794.

While that fiery figure clearly represents Urizen, another engraving, with a younger figure, is the one usually designated "fire." That one (Fig. 18; photo by Ela Howard from Beinecke Library copy of Blake) is of Urizen’s son Fuzon, who, Blake says, “flamed out, first begotten, last born” (VIII.3.9). Erdmann identifies the figure as Los, fiery imagination. That is something that bursts out of Lear, too, as we shall see.

Figure 19. Utha (Water), from William Blake, First Book of Urizen 1794.

In another engraving (Fig. 19; Ela Howard photo from Beinecke Library), a figure floats in water, barely conscious. The son is Utha, who “from the waters emerging, laments” (VIII.3.7). This state is Lear's during the storm; while lamenting, to be sure, in his case a rigid ego is loosening, to float before rebirth. Similarly, Blake’s figure seems to be drifting more than he is swimming. As for Urizen, what corresponds, according to Erdmann, is his “hiding in surgeing Sulphureous fluid his phantasies” (IV.2.3-4). Hiding his fantasies, Urizon’s ego does not loosen. Lear, on the contrary, does not hide his fantasies, and thereby opens himself to the possibility of transformation.

Figure 20. Thuriel (Air), from William Blake, First Book of Urizen, 1794

Another engraving represents air (Fig. 20 above; Roob 2001, 213). The figure is Urizen’s son Thuriel, who appears “Astonished at his own existence,/ Like a man from a cloud born” (VIII.3.5-6). ). Erdmann sees him floating in the sky, bounding against either clouds or rocks. For Uruzen, the image corresponds to his state at the beginning, when he is still in the void but “searching for a solid without fluctuation” (II.4.6), and also at the end, after his sons and daughters have populated the earth. Blake says, “Cold he wandered on high, over their cities/ In weeping & pain & woe” (VIII. 6.1-2). Lear’s state, as it develops, becomes less anxiety-ridden. In the morning after the storm, his speech, a reversal of many of his previous attitudes, is full of “Reason in madness” (IV.vi.168), and he bounces airily from one mood and subject to another.

Figures 21 left: 15th century Alchemical manuscript; Figure 22, center, Thuriel/Air in Beinecke Library copy of Urizen; Figure 23, right: "Charles VI" (also called "Gringonneur") tarot Hanged Man card, from c. 1560 Florence, Italy.

In addition. I see a likeness between Blake’s image to the “upside down man” of alchemy and the Hanged Man card of tarot (Fig. 21, alchemical image from Dixon 2003, 256, Bosch; combined with Fig. 22, a different version of Fig. 20, photo by Ela Howard from Beinecke Library's copy; and tarot card from Innes 1987, 40). The alchemists envisioned the vapor that rises from their liquid as Mercury in upside-down form, perhaps because of the drastic change of position from bottom to top of the retort. A similar analysis applies to the Hanged Man. In tarot this card is also called “the traitor,” of whom the chief representative is Judas (Moakley 1966). An incident connects the card with the father of the man for whom the first extant tarot deck was made, Francesco Sforza. Muzio Attendolo, called “Sforza” or strength, was chief condottiere, or strong man, for the Lord of Milan in the early 15th century. He also aided the pope based in Rome (as opposed to the one in Avignon), who made him a count for his services. Later Muzio offered his services to an enemy of that pope. The pope retaliated by posting a picture of Muzio in the “Hanged Man” position on all the bridges and gates of Rome (Maokley 1966). For the Sforzas, then, the card would be easy to remember by association with this incident (Dummett, 1986, argues persuasively that tarot was originally a game like bridge, in which players won tricks using trump cards, trionfi, or triumphs. Thus they had to remember what trumps had already been played.) The picture thus signifies not simply betrayal but a reversal in allegiance or attitude, for better or worse. Lear in the end achieves just such a reversal, and Blake’s Urizen as well.

Urizen’s four sons correspond to four of the five stages in my interpretation of the alchemical illustration of Fig. 14 above. The fifth stage, air augmented by fire, is somewhat captured in the image of Los, Fig. 18. Urizen does not in this poem get even to the stage of Air, where release of his fantasies would allow him to reverse his former rigidity. Urizen must continue to suffer through several more of Blake’s prophetic books, until Blake finally redeems him in Jerusalem The Emanation of the Giant Albion. We shall continue to follow Urizen’s progress.

Figure 24. The net of religion. From William Blake, First Book of Urizen, 1794.

At the end of Blake’s poem, its protagonist is bound once again (Fig. 24; photo by Ela Howard of Beinecke Library's copy). The pose is as on the title page, except that now he is weighed down by rope netting on both sides. The poem relates that as Urizen wandered, “a cold shadow follow’d behind him/ Like a spider’s web, moist, cold & dim” (VIII.6.5-6). It settled over him, and:

None could break the Web, no wings of fire,This net spreads over the earth as well; such is the lot of humanity. In contrast, the alchemical process is one of transformation, as we have seen in the alchemical illustrations and to a degree in Blake’s images of Urizen’s sons. Another that especially fits Lear is from an alchemist of Antwerp, Hermann Hugo (Fig. 25 below; Roob 2001, 228). A young man looks up hopefully through the skeleton of his former self, no longer the giant he once appeared to himself to be. The Gnostics, as we have seen, anticipated both outcomes.

So twisted the cords, & so knotted

The meshes, twisted like to the human brain.

And all called it The Net of Religion. (Urizen VIII.7.5, 8.1-2, 9)

Figure 25, from Hermann Hugo, Pia Desideria, 1659.

No comments:

Post a Comment